Dear Artists, Don’t Stick Your Head In The Sand

/Imagine one day you decide to start a podcast. You're very excited about your new venture and spend countless hours researching topics, writing copy and setting up your recording booth just so. But you know that if you want people to listen, it needs to be entertaining, and 45 minutes of you talking into a microphone won’t be. It's got to be a real multimedia experience; that's the difference between entertainment and lecture. Among other things, you'll need music, maybe some sound effects, and even archival audio material to spice things up.

So where do you find those things? And when you find them, do you properly attribute them? Do you request permission to use them and pay a fair licensing fee? If there’s something specific you want, do you make a good faith effort to find the owner, or do you just take it? If you don’ have satisfactory answers to these questions, you may want to rethink your strategy before you hit "publish."

One hallmark of being an artist is excitement about your latest work and a strong desire to get it out into the world. You want people to see it, to comment on it, and hopefully, to enjoy it. Any artist who claims otherwise is lying - to you or themselves. It's easy in that situation to get tunnel vision and let caution fall by the wayside. When momentum is on your side, why get bogged down in administrative matters?

I understand that impulse as much as anyone. I've been an artist (I like to think I still am) and I see it with my clients. But I want to take this space to urge you, dear artists, not to stick your head in the sand and assume no one will care about those administrative matters. Even if you don’t, I promise you someone else does. I’ve long advocated on this blog for sweating the business stuff because being an artist these days means being a business owner - whether or not its formalized and even if it's not a primary means of income. Using the copyrighted work of another without permission puts you and your business in jeopardy. Maybe not today and maybe not tomorrow, but eventually someone is going to notice, and they're not going to accept "I didn't know" as a reasonable excuse.

It's tempting to pin your hopes on fair use, but the problem with fair use is that to prove you’re covered by it, you need to defend yourself, which almost certainly means thousands of dollars in legal costs. Some courts view fair use as a right, while others view it merely as a defense (which means you can't assert fair use until AFTER you've been sued), but practically speaking, the only way to know for sure whether fair use applies is for the litigation to play out. Just saying the words "fair use" is no more a shield against litigation than yelling "I declare bankruptcy" a way of erasing debt.

We live in a litigious society. And IP holders, especially large corporate ones, have no compunction about hailing little guys into court over minor infractions. Defending yourself will take money you don’t have, and months or years out of your life. Sometimes, companies go bankrupt simply defending themselves in court. I can assure you that even if you win, it’s not worth it.

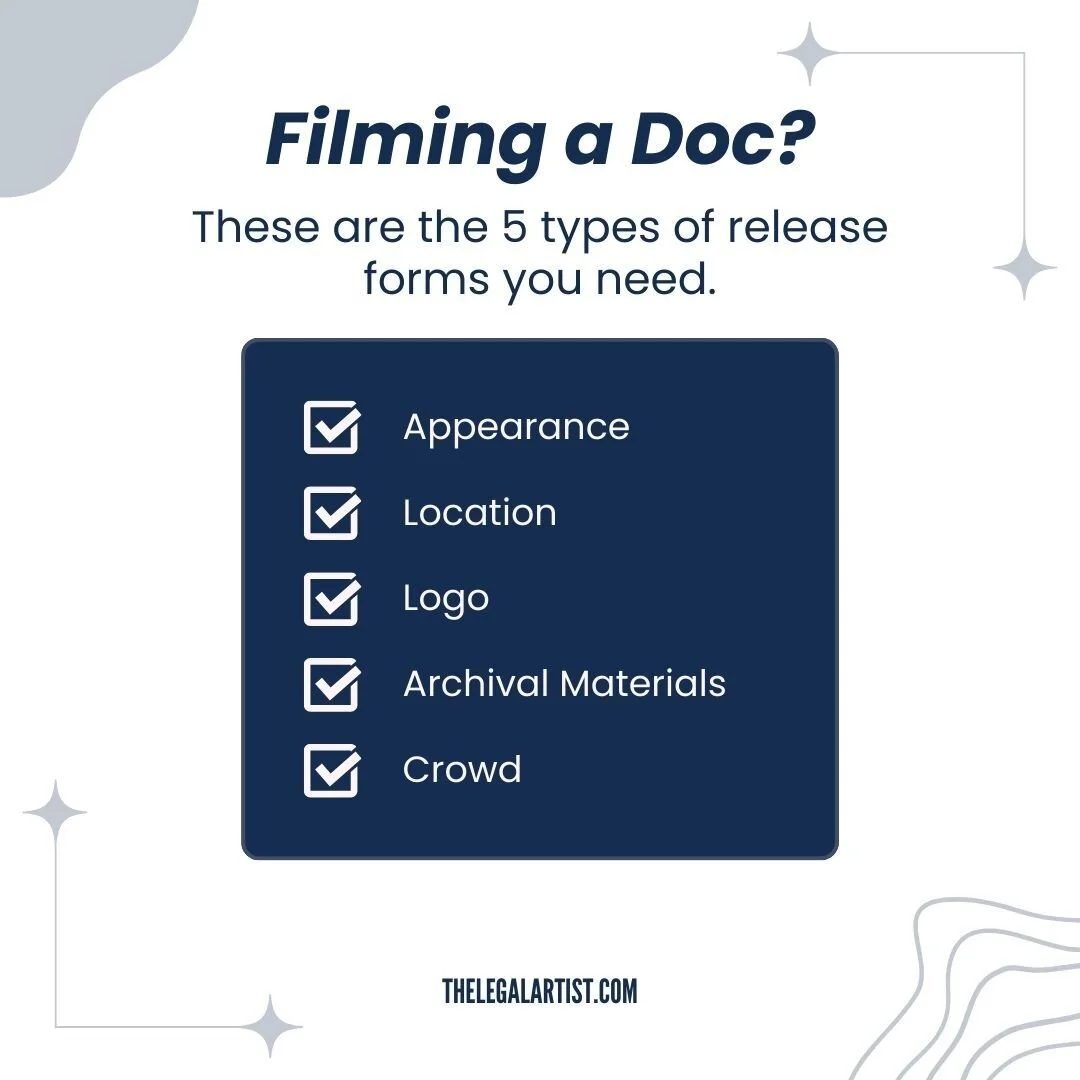

Which means - let’s say it together - you have to sweat the business stuff. You need to have things like contracts, bills of sale, release forms, licensing agreements, and business bank accounts. It means you probably have to incorporate your business. It means you can’t rely on fair use unless a lawyer tells you it’s okay. It means you have to ask permission to use work you didn’t develop. There’s a lot more to it than that, but you get the gist.

Don’t stick your head in the sand, hoping that ignorance will save you. Pay attention to the administrative matters. Build it into your schedule and workflow. If you hate doing it (welcome to the club), have a friend or spouse or family member help you. I’m not trying to rain on your parade. I’m here to tell you the rain is coming one way or another. I just want to make sure you have an umbrella.